New light on the location of Clément Marot’s

tomb and epitaph in Turin

Article published in Studi

Francesi n. 161/2010

[anno LIV - fascicolo II - maggio-agosto 2010], 293-303

SUMMARY: That the French court poet

Clément Marot (born in Cahors in 1496) died in Turin in 1544 has always been

known; that his life-long friend Lyon Jamet wrote an epitaph for his tomb and

had it engraved in marble, also. That the epitaph was effaced and the tomb could

not be found was generally accepted. Re-combining factual information consisting

of sixteenth-century references (Audebert’s Voyage d’Italie and

Gianbernardo Miolo’s Cronaca, both not new but almost passed into oblivion), the author

reconstructs the circumstances around Marot’s burial, identifies the

commissioner, and claims that the epitaph, although effaced, can be located

almost exactly in the Cathedral San Giovanni in Turin. A recent discovery of a

contemporary drawing of the original epitaph makes a virtual reconstruction

in loco possible.

Marot's epitaph in Turin - more info at the end of this essay]

To refresh the minds of the

connoisseurs, and to introduce the others to the issue at stake, I first

present a short survey of the state of the question about Clément Marot’s

arrival and stay in Turin, trying to distinguish between known facts (F) and

probabilities (P)

-

After having left Geneva in 1543 on an unknown

date, but (F) after October the 15th, when Jean Calvin pleaded at the Geneva

council for a pension to support Marot,[1]

and (P) before 20/12/1543, when Marot’s name is mentioned but he himself is

not summoned for the Consistory in the so called tric-trac affaire.[2]

-

(F) Marot spent some time in the Savoy, i.c.

near Annécy with Bonivard’s sister in law, Pétremande de la Balme (to whom

he dedicated an epigram[3])

and with a friend of Bonivard, François Noel de Bellegarde (near Chambéry),

a man of some stature and political weight in the Savoy, to whom he also

addressed a poem.[4]

-

(P/F) Marot tried to move the King’s heart to

let him return to France. Some epigrams testify to this effort.[5]

-

(P) While in Chambéry he must have heard of

the preparations for battle and the subsequent victory of the Comte

d’Enghien (François de Bourbon) near

Ceresole (14 April 1544). (F) In an Epistle - "Epistre A Monsieur d’Anguyen"

- Marot offers his services to the

conquering hero and in an epigram he sends his best wishes to his military

camp.[6]

-

(F) He ventured south from Chambéry and (P)

via the pass of Col Mt. Cenis and the valley of Susa, he arrived in Turin,

the headquarters of the King’s governor.[7]

-

(F) On 12 September September Marot died.

-

(F) Lyon Jamet wrote an epitaph for his tomb,

which was engraved in marble and placed in the Cathedral San Giovanni in

Turin.[8]

At this point there is some

confusion, because some authorities suggest that Marot died in the

Ospedale san Giovanni Battista

and that Jamet had the epitaph inscribed

on his tomb there. The heading with which the epitaph of Jamet is

published (at least generally known since Lenglet Du Fresnoy (1731) placed it in

front of his edition of Marot’s works) is quite explicit:

Epitaphe sur le tombeau de Marot, Faict par Lyon Jamet, insculpé

en marbre en l’Eglise Saint-Jean de Turin, 1544, le 12 septembre.

The Turin cathedral is dedicated

to San Giovanni, i.c., John the Baptist.

[9]

“A la recherche du tombeau

perdu”

Of course people have searched

for traces of the tomb and the Epitaph, but in vain:

|

|

-

Nicolas Lenglet Du Fresnoy

(1674-1755), Marot’s first modern editor, writes in a footnote (Oeuvres vol. I,

p. xxiv, 1731) below the text of the Epitaph: “J’ai prié un de mes amis qui

alloit en Italie de voir en passant à Turin, si cet Epitaphe de Clement Marot se

trouveroit encore dans l’Eglise de St.Jean, où Lyon Jamet l’avoit fait graver.

Mais toutes les recherches ont été inutiles; soit que Marot ayant donné dans les

nouvelles opinions, on ait depuis oté cet Epitaphe, soit que le temps l’ait

effacé ou fait oublier.”

-

Georges Guiffrey

(1827-1887), the first one who tried to establish a critical edition of Marot’s

works, went to Turin himself (not so far, he was senator of the dep.

Hautes-Alpes) to look for any trace of it. This is his report (Oeuvres,

vol. I, p. 561): “Nous avons fait le voyage de Turin pour rechercher dans

l’église Saint-Jean la pierre sous laquelle devait reposer Marot; Nous n’avons

pu découvrir le moindre vestige de cette sépulture…

A défaut de

la pierre funéraire qui peut-être fut enlevée au milieu des vicissitudes de la

politique, ou dont l’inscription fut effacée par les pas des fidèles, nous avons

tenté d’interroger les archives obituaires de l’église.

Ces archives

s’arrêtent brusquement quelque temps avant la mort de Marot. Le temps a ses

caprices…”

|

|

|

|

Before continuing, a preliminary

question needs to be dealt with: How it is possible that a French poet with a

‘protestant’ reputation was buried in the Archbishop’s Cathedral, a poem in

French being carved out in marble and placed above the tomb? The level of

amazement can already be considerably lowered when one takes into account the

historical context: After the battle of Ceresolo Turin had become the

headquarters of the conquering army, and thus the centre of French dominion. In

1544 the term ‘protestant’ was not yet cleared out: many people were longing for

and working on a reformation of the Church; in and around Turin the Vaudois

community was prominent; the region of Piedmont was known as a safe haven for

many a refugee from France;[10]

and finally the (unifying) influence of John Calvin should not be overestimated

yet: his dominance was only emerging. One should not project (or better:

retroject) simple oppositions of later days to times when they were only

in

statu nascendi. But there is more to this than placing the facts in a

historical perspective alone.

Marot was not just ‘anybody’; he was the ‘prince des poëtes francoys’. The usual

suggestion that Marot lived and died in poverty the last months of his life in

Turin, desperately – but in vain – trying to get restored to his former glory

(the favour of the King) is not based on fact; On the contrary: the few known

facts seem to point in the opposite direction. A contemporary witness to Marot’s

burial, Gianbernardo Miolo (1506 - after 1569, since 1539 a notary employed

by Gullielmo of Cercenasco, a village near Turin), informs us that the King’s

Ambassador in Rome, George d’Armagnac

(at the end of the year he is offered the cardinal’s hat), carried the expenses

for the burial of Marot.[11]

This simple communication is revelatory, but seems to have eluded the attention

of Marot scholars. George d’Armagnac was not only the King’s ambassador, but

also Marguerite de Navarre’s protégé. She had introduced him at Court. He became

one of France’s most influential diplomats, friend of Princes and Popes, and

great lover of the Arts.[12]

He is suggested to have commissioned the burial and commanded the placement of

the epitaph, something which seems quite imaginable. Perhaps the author of the

Epitaph, Lyon Jamet, was the one who in loco

took care that everything

went as foreseen. Him we often only know as Marot’s friend, but he was much more

than that. He was seigneur de Chambrun and an international diplomate.

Ever since his flight to Ferrara, slightly preceding Marot’s arrival there, but

having fled for the same reason (he was on the list of wanted persons after the

Affaire des Placards), he was at the service of the Duchess ànd the Duke

of Ferrara,

which is quite extraordinary regarding his ‘protestant’ stigma. As the Duke’s

personal secretary and ambassador he fulfilled many an important mission, both

in Italy and France.[13]

Behind these two men, two of the most powerful female friends of Marot:

Marguerite de Navarre and Renée de Ferrara, become visible by implication. They

are the true instigators of his prominent burial place. Marot was not living an

obscure life in Turin, nor did he die unnoticed. Prominent persons took care of

his final resting place, which therefore should be worthy of France’s most

eminent poet: in the Cathedral of Turin, the Duomo San Giovanni.

|

|

.jpg)

|

|

François de Bourbon, count

of Enghien,

general of the French Army in Italy in 1544

picture: Corneille de Lyon

|

The 'Memoires' of Martin du Bellay,

brother of Jean (Cardinal) and Guillaume (Diplomat),

one of the Turin governors in 1544.

|

Nicolas Audebert’s description of the burial place and

the Epitaph

In 1962 Adalberto Olivero dug up

and published ‘new’ (i.e., once more, ‘old’) information about the exact

location of Marot’s tomb and epitaph; information he had found in a Manuscript

in London, containing Nicolas Audebert’s report of his Italian journey of

1574-1578, Voyage d’Italie.[14]

Audebert writes – with indignation – that Marot’s epitaph in Turin was erased

just before his arrival. He mentions as a matter of fact that this was

explicitly demanded by the roman-catholic authorities. Next to the very precise

date and circumstance, already noteworthy, the most interesting element of Audebert’s description is that he also indicated the exact location of tomb and

epitaph. To give the reader the opportunity to follow, we copy the transcription

as published by Olivero:[15]

Tout contre et à un

bout du palais est la principale et Cathedrale eglise nommée San Giovanni,

laquelle est très belle, grande et spatieuse.

Il y a deux entrées l'une qui est tout au

bout, et de premiee arrivée regarde droict au maistre aultel, à laquelle se

monte dix ou douze marches de pierre de taille.

L'aultre porte est petite

et à main droicte, devant laquelle y a un petit perron pour venir en l'eglise et

soubz iceluy est ensepulturé Clement Marot

duquel l'epitaphe estoit tout

proche, au dedans de l'église, en une pierre longuette qui est dans la muraille,

laquelle a[16],

depuis peu de temps,

esté martellée et l'Epitaphe effacé, par l'advis et requeste de l'Archevesque,

et rnaistres de l'inquisition, avec le consentement de son Altesse, ce que

Madame la Ducesse avoit longtemps empesché et rompu le coup quand il s'estoit

proposé.

Il n'y avoit en l'Epitaphe

qu'un dixain en vers francoys, telz qu'ilz suivent qui furent faicts par un

aultre poete francoys nommé Lyon Iamet.

Icy devant au giron de sa

mere

Gist des Francoys le Virgile

et l'Homere

Cy est[17]

couché, et repose à l'envers

Le non pareil des disans en

vers.

Cy gist celuy qui[18]

peu de terre coeuvre

Qui toute[19]

France enrichit de son oeuvre

Cy dort un mort, qui

tousjours vif sera

Tant que la France en

Francoys parlera.

Bref gist, repose, et dort en

ce lieu cy

Clement Marot de Cahors en

Quercy.

le 12 septembre 1544

Audebert renders the epitaph in

a version almost identical to already known editions. According to his own

report, he did not actually see the original epitaph, since it was already

effaced when he arrived in Turin. The information about the circumstances in

which the epitaph was demolished, seems trustworthy. One gets the impression

that Audebert reproduces information he got while in Turin. Something of fresh

felt indignation shimmers through his text. Apparently the epitaph was

demolished shortly after the death of Marguerite de France (15 September 1574),

she also being the only reason that this was not done before. The Archbishop,

Girolamo della Rovere, was educated in France, acquainted with the poets of the

Pléiade, and tried to implement the Tridentine reform. The consent of the

Duke of Savoy can also be understood. He not only supported the new archbishop,

but seemed to have had high expectations of the Jesuits:[20]

signals that both opted for a re-catholisation of the Waldensian region and

therefore were willing to cooperate with the ‘masters of the inquisition’ to

erase Marot’s epitaph in the Cathedral. Marot’s ‘fama lutherani’, during his

lifetime already inextricably bound to his person, had only increased after his

death, in particular because his Psalms were sung in reformed liturgy. Next to

these religious motives, one should also not underestimate anti-French

sentiments in Turin/Savoy in those years. The French occupation (from 1536) had

ended in 1559, when the duke of Savoy (Emanuele Filiberto) had succeeded in

transforming his duchy into a powerful political player in the region (peace of

Cateau-Cambrésis). Italian became the official language and in the centuries to

come the Duchy of Savoy became a stable and unifying factor on the hopelessly

divided Italian peninsula. This relative independence (both from Spain and

France) of the Duchy of Savoy coincided with the Duke’s marriage with the

daughter of François I, Marguerite de France. The personal attachment of

Marguerite de France (1523-1574) to the ‘monumentum’ for Clément Marot can also

be understood: She must have known him personally, Marot was her father’s

official poet; as a young girl she even once had received an Epistle from her

niece (Jeanne d’Albret), which in reality was written by Marot.[21]

As a girl from François’s first marriage (with Claude de France, d. 1524), she

was raised by her aunt, Marguerite d’Alençon, Queen of Navarre, Marot’s most

loyal supporter and protector. Cultural interest, spiritual open-mindedness, and

readiness to personally protect religious refugees, mirror her upbringing. This

valuable information provided by Audebert, made available by Olivero in his

article in 1962, did not really attract attention of the scholars in het last

part of the twentieth century.

In his biography of Marot (1972),

Mayer obscures this when he, in a footnote referring to the article of A.

Olivero (!),

only writes: “Peu de temps après l’Inquisition semble avoir enlevé

toutes traces de ce tombeau. Déjà au dix-huitième siècle il était introuvable.”[22]

Location of Tomb and Epitaph in the Duomo

But what is even more

astonishing, is that the very precise indications about the location of Marot’s

final resting place and the Epitaph inside the Church seems completely to have

eluded the eyes of modern scholars, since I could not find any reference to this

in subsequent literature. Nevertheless it can’t be more precise. Audebert gives

accurate directions, as if he wants to guide the reader to the proper place. To

find Marot’s grave the visitor should not enter through the main entrance but

take the smaller door at the right-hand side of the Church.

-

In front of this door is a landing, pavement

(‘perron’). Here Marot is buried (“et soubz iceluy est ensepulturé Clement

Marot”)

-

To find Jamet’s epitaph one should enter the

church through that door, and look for the epitaph, since it should be

nearby (“duquel l'Epitaphe estoit tout proche au dedans de l'église”);

-

It should not to be looked for on the floor

(as Guiffrey did), but on the wall (“en une pierre longuette qui est dans la

muraille”

-

One should not expect to find it, since it was

completely demolished and cut off (“martellée”). Nevertheless the location

might still be determined.

Based on this information an

“expedition” to Turin forced itself. Although no expert in architecture and

inscriptions at all, and with only a very general knowledge of the history of

Turin, this could never be more than prospecting to size up the situation and

determine whether a further investigation would be worthwhile. The results – as

described below – I offer to real experts ‘as they are’, i.e., without any

pretension, hoping they might incite them to make the proper assessments in

loco.[23]

The ‘small entrance at the right-hand side of the Cathedral’ was quickly found.

The space in front of it, where the ‘perron’ used to be, serves as an office to

the parish of San Giovanni. The space below, where Marot originally was buried,

is now used as the entrance of the museum. The many changes, restorations and

transformations made it highly unlikely that the bones of Marot would still be

there, but the location of the burial place itself seems certified.

|

|

|

|

1a. outside view |

1b. inside view |

Ever since the remnants of the

old churches were discovered under the existing church (restoration of 1997,

after the great fire), archeologists and architects have taken over to uncover

and interpret the presence of ‘a complete second church’ below the ‘upper

church’, apparently also meant for devotional use. Next to the remnants of three

palaeo-christian churches, they found and identified the bones of Cardinal

Domenico della Rovere

(d. 1501), bishop of Turin and driving force behind

the construction of the Renaissance cathedral completed in 1498.[24]

These excavations brought to light that not only the crypt below the sacristy (a

little further at the right side of the choir) was used as an ossuary: burial

places were found all along the outside church walls.[25]

One is still in the process of making the inventory.

|

|

|

2. profile - longitudinal section –

of the Duomo (with the contours of the chapel of the Holy Shroud, a

later addition). The entrance is between the 6th and 7th

pillar, just before the transept. |

It is apparent that in the early

days of this Cathedral this area was used for burials, elements not only

corroborating the account of Audebert about the ‘perron, soubz iceluy est

ensepulturé Clement Marot’, but also providing it with the necessary context to

make it imaginable.

The church itself is full with

epitaphs and funerary monuments, many of them placed on the wall, engraved in

marble. According to Audebert’s report Marot’s epitaph was located inside the

church, on a stone in the wall, not far from the door (‘tout proche au dedans de

l'église en une pierre longuette qui est dans la muraille’). Both walls close to

the door were equipped with inscriptions. To the right (when entering the

church) there is an inscription, beautifully carved in marble with an elevated

border. Above the text is the coat of arms of a noble family (the inner part is

vanished, only the outside shape is visible). It must belong to the marquisat of

Ceva, since according to the Epitaph a marquis of Ceva, named Cristoforo,

was buried there (‘Christophorus marchio Cevae’).[26]

|

|

|

|

3. Epitaph of Cristoforo di Ceva (at the

right-hand side from the door on entering the Church) |

3b. The entire stone with the impression

of depth (no flash, therefore unsharp). |

The reason why he was buried in

the Turin Cathedral is also mentioned: He was related to (‘nepos’) Domenico

della Rovere himself, in the text simply referred to as the cardinal of S.

Clemente (‘cardine[us] Sancti Clementi’). Cristoforo di Ceva died 15 May

1516. We can assume that the stone was fix and firm at that particular place

when in 1544 Jamet’s epitaph for Marot was to be placed on a wall near the door.

On the opposite wall (left when

entering the church) a stone remembered that that Claude Guichard was

buried there, counselor and historiographer of the Duke of Savoy, a famous

archeologist (specialized in ancient funeral rites) and French poet as well. The

epitaph informs us that he had died 8 May 1607.[27]

|

|

|

4. Epitaph of Claude

Guichard (at the left-hand side from the door on entering the

Church) |

This epitaph postdates the

removal of Jamet’s inscription with 33 years. It therefore is quite possible

that this was the wall ‘tout proche’, on which until 1574 Jamet’s Epitaph could

be read. We took a closer look and noticed something odd. Contrary to the

epitaph on the opposite wall (and many others in this church), this epitaph was

not carved out beautifully in marble, with a border as so many others in the

church; it appeared to be not even really engraved: it was more painted

on the stone than carved in it. A rectangular space in a whitened wall. Taking

an even closer look, we noticed roughness at the place where the upper and lower

border (but it was no border, the white painting simply stopped there), as if

something had been cut off and the surface was not properly smoothed. Of course

the church has been damaged, restored and repainted many times. And perhaps

there is another explanation for this peculiarity, but nevertheless: looking at

this post-Audebert inscription, it seemed quite imaginable that his inscription

covered the place of a previous one, that of Jamet’s epitaph for Marot, which

had been removed by force (“martellée”).

[28] All elements fitted:

not far from the right side door…

just inside

the church…

Although we had not seen Jamet’s

epitaph with our physical eyes, we had the strong impression of having seen it

with our spiritual eyes, a minor but sweet revenge on those people who had so

vigorously tried to wipe out all traces of Clément Marot de Cahors en Quercy.

La mort n’y

mord

Antwerp, 25 July

2009 // Dick Wursten & Jetty Janssen

Post Scriptum

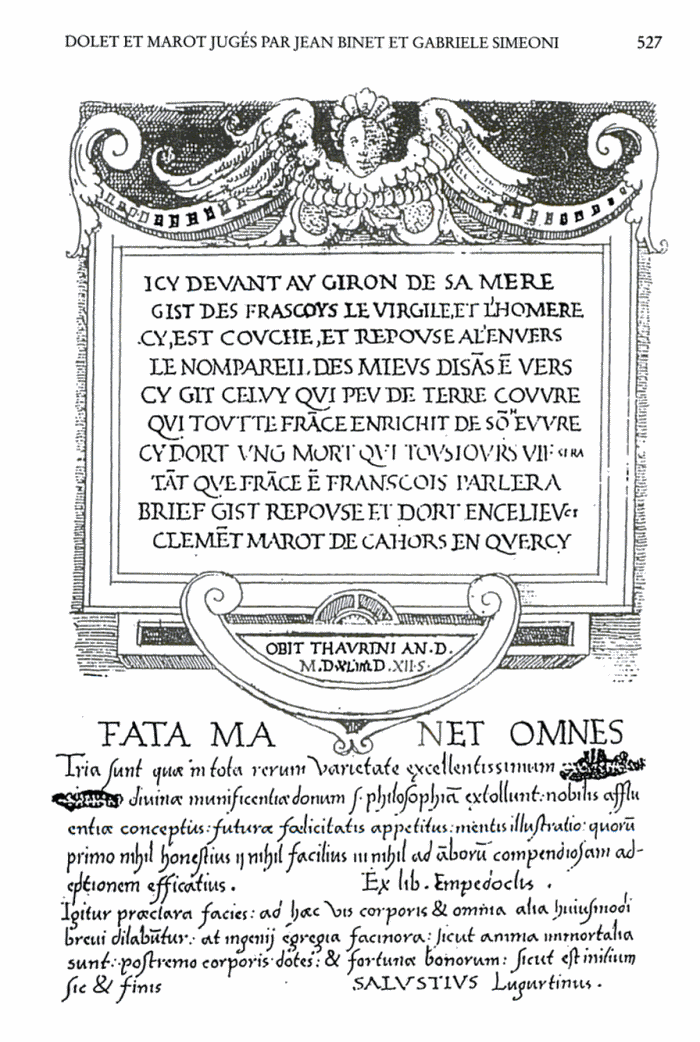

After

returning home, having done the research to write this article, our attention

was drawn to a recent publication by Richard Cooper, in which he relates that he

found an image of the original epitaph in Turin, a drawing by a student, who in

the middle of the sixteenth century travelled through Italy, Spain, Germany and

France setting down epitaphs and other inscriptions. His Manuscript ends with

two epitaphs dedicated to Marot, the final one being Jamet’s.

(Harvard,

Houghton Library, MS Typ 152, f° 179v°,

Imagines

sepulcrorum et epitaphiorum inscriptiones antiquae.) See, Richard Cooper,

‘Dolet et Marot jugés par Jean Binet et Gabriele Siméoni’, in Esculape et

Dionysos: Mélanges en l’honneur de Jean Céard, ed. Jean Duprèbe, Franco

Giacone, Emmanuel Naya (Geneva, 2008), p. 511-527, the discovery on p. 522-523,

the reproduction at p. 527. The text of the epitaph in majusculs with

abbreviations and orthographical errors (which at the same time betray that the

one who carved it probably was an Italian and that the drawing is not fake)

closes with: “Obit Thaurini An.D. M.D.XLIIII. D.XII..S.” (‘he died Anno Domini

1544 on the 12th Day of September’). The space used for Guichard’s

epitaph and the space needed for Marot’s seem to match.

The drawing of this

wandering student is reproduced heading this article, the entire page below (copy from the article of Richard Cooper,

p. 527).

“Maistre Calvin pour Clement Marotz. – Le sieur Calvin a exposé pour et

au nom de Clement Marotz requerant luy faire quelque bien et ilz se

perforera [usually emended: se parforcera] de amplir les seaulme

de David. Ordonné de luy dire que pregnent passience pour le present.”

(P. Pidoux, Le Psautier Huguenot, vol. II (Basle, 1962), p. 23.

The story can be read in the minutes of the Consistoire from 18 &

20 December 1543 (Registres du Consistoire de Genève,

vol.

I, p. 287‑295). Also extracts in Pidoux II, p. 23‑24). The games that

are mentioned are dames, jeux des cartes, dés,

and

tricquetract and the core issue is to identify the ‘prédicant’ from

Orbaz (Pidoux transcribed ‘Orléans’) who is suggested to have

participated in a game played for money. Reading between the lines, one

can deduce that François Bonivard (Seigneur of St. Victor), Clément

Marot and Aimée Curtet (a syndic) met regularly to play.

“Adieu ce bel oeil tant humain…” (Clément Marot, Oeuvres Poétiques,vol.

II, ed. G. Defaux, p. 337‑338).

A ung sien amy (Defaux II, p. 703‑705). We do not take into

account the anonymous epistle addressed to M. Pelisson XE "Epistre A

Monsieur Pelisson, President de Savoye*" (president of the

Parlement of Chambéry):

A Monsieur Pelisson, president de Savoye,

1543, (Defaux II, p. 705‑707). The author of this epistle has only

recently arrived in Savoy coming from Paris/France (v. 35). The implicit

chronology is irreconcilable with established elements of Marot’s

chronology, who left France in 1542, stayed in Geneva for about a year.

Discussion of the authenticity in Mayer, vol. 1 [Les Epîtres], p.

62‑63 (rejection), and in Defaux II, p. 1292‑1294, cf. p. 1122

(acceptance of the authenticity, but not successful in accounting for

the chronological problems implied). That the epistle is too feebly

constructed and old-fashioned to have been written by Marot, is perhaps

not a cogent argument contra (Defaux makes this point against Mayer),

but it has some relevance; it at least does not counterbalance the

simple bibliographical and text-internal argumentation as presented by

C.A. Mayer (following Pierre Villey).

A ‘placet’: “Plaise au roy congé me donner / D’aller faire le tiers

d’Ovide…" (Defaux II, p. 710). ‘Le tiers d’Ovide’ refers to the

translation of the Metamorphoses by Marot; a

Dizain au Roy.

envoyé de Savoye. 1543 (Defaux II, p. 319; first publication 1547

(Marnef); also present in Du Moulin and Fontaine’s selection of Marot’s

Oeuvres, so bibliographically as ‘certain’ as possible).

This epistle was published separately in 1544 by N. L’Heritier (Mayer,

n° 121, Defaux II, p. 707). The epigram Salutation du camp de

Monsieur d’Anguiers appeared in print in 1549 in an edition of

Marot’s Oeuvres by Jean de Tournes (Mayer n° 169, Defaux II, p.

338). The style and content of this epigram leave open the possibility

that Marot had already joined the camp before the actual battle.

The final phrase in l’Histoire ecclésiastique

concerning Marot

suggests the same: “…il s’en alla passer le reste de ses jours en

Piémont, alors possédé par le roy, où il usa sa vie en quelque seureté

sous la faveur des gouverneurs.” (Histoire Ecclésiastique des Eglises

Réformées, vol. 1, ed. P. Vesson (Toulouse, 1882), p. 20; reprint

from the 1580 edition, ascribed to Th. de Bèze. One of the actual

governors at that time was Martin du Bellay, brother of Guillaume, who had

been governing the province of Piedmont until his death in 1543.

The epitaph was published in Cinquante Deux Psaumes de David

(Paris, Jacques Bogarde, 1546), Mayer n° 149. Already on 1 October 1544

(date of the privilege) a Déploration de France sur la mort de

Clément Marot, son souverain poëte, appeared in print in Paris. See

Guiffrey I, p. 563. For the text of this epitaph, see Mayer Clément

Marot , p. 514-515 (idem in Defaux II, p. 1187). Guiffrey I gives

the text as published by Roville 1561.

An Ospedale San Giovanni indeed existed. It was even officially

(re-)instituted in 1541in an effort to improve social welfare by

centralising all city hospitals in a modern building near the Duomo

(Sandra Cavallo, Charity and Power in Early Modern Italy -

Benefactors and their motives in Turin, 1541-1789, [Cambridge

History of Medecin] (Cambridge, 1995), p. 12-14. The hospital only

received a proper building near the cathedral in 1545.

The first occurrence of Marot being buried in the

(chapel of) the hospital, I found – but I don’t claim completeness – in

1914 with Ph.A. Becker in the final part of his biographical essay

‘Marots Leben’,

Zeitschrift für französische

Sprache und Litteratur 42 (1914), p. 205:

“Marots Leiche wurde im Ospedale San Giovanni Battista in Turin

beigesetzt, und sein alter Freund Lion Jamet setzte ihm die

Grabschrift.” In 1926 (in the introduction to his biography) Becker

himself classified this text as premature, though leaving this error

uncorrected (Clement Marot, sein Leben und seine Dichtung, p.

183). The same error I also found with Henri Guy (1926, Clément Marot

et son école, p. 320 ); Pierre Jourda (1950/1967,

Clément Marot,

p. 58) ; C.A. Mayer (1972, Clément Marot, p. 515, and G. Defaux

(1990, Oeuvres Poétiques t. I, p. clxvii). The fatality of such a

copying attitude is that the misinformation is raised to the status of

fact. E.g., as such it is presented in the popular biography by Jean-Luc

Déjean, Clément Marot (Paris, 1990), p. 383-384 : “Ce dont nous

sommes sûrs, c'est qu'il [sc. Jamet] arriva à point pour lui donner des

funérailles décentes, dans le cimetière de l'hôpital Saint-Jean-Baptiste

à Turin. Il orna la tombe d'une plaque de marbre portant une épitaphe de

sa façon.”

See J. Jalla, ‘Le refuge français dans les vallées Vaudoises’, in BSHPF 83 (1934), p. 561-592 ;

BSHPF 85 (1936), p. 5-25. He

writes about the beginning of the 1540s : "La tolérance religieuse était

tellement plus grande en Piémont que dans les autres provinces de la

monarchie française, que cette région servit de refuge à plusieurs de

ceux qui étaient traqués au-delà des Alpes." (p. 573). For a general

assessment of the Vaudois movement, id. Storia della Riforme in

Piemonte (Torre Pellice, 1914; reprinted in 1982).

Cronaca di Gianbernardo Miolo di Lombrascio notaio. The notes

concerning the events that happened during his lifetime, were extracted

from his manuscript by Giuseppe Vernazza and prepared for print in 1771.

Vernazza comments on Miolo’s style and notes: “Lo stile adoperato dal

Miolo è rozzo latino, ma dappertutto risplende la buona fede e la

natural franchezza della verità.” These ‘Notizie’ were published in

Miscellanea Storia Italiana, vol. 1, ed. Regia deputazione di Storia

Patria (Turin, 1862), p. 145-233. The quote about Marot’s funeral is

placed at the end of a detailed account of the main events of 1544 of

the region (including the battle at Ceresole). Miolo apparently did not

know the exact dates, since normally his chronicle is full of exact

dates ordered chronologically. As a kind of Post Scriptum to the events

of 1544, he writes: “De anno eodem 1544. Taurini Clement Marot gallus in

rittimis galicis clarissimus moritus. et in templo archiepiscopali

inhumatur expensis Georgii cardinalis Armeniaci.” (p. 184). Jalla, a.c.

p. 576 (see above note 10)

and A. Olivero in his edition of Nicolas Audebert’s Voyage d’Italie,

(Rome, 1981), p. 291 both refer to Miolo’s chronicle.

George d’Armagnac (1501-1585) was portrayed by Tiziano Vecelli (now in

Musée du Louvre). For him, see Salvador Miranda, The Cardinals of the

Holy Roman Church, Essay of a General List of Cardinals (112-2007),

http://www.fiu.edu/~mirandas/bios1544.htm#Armagnac.

On Lyon Jamet, see Rosanna Gorris,‘"Va lettre, va ... droict à Clément’:

Lyon Jamet, sieur de Chambrun, du Poitou à la ville des Este, un

itinéraire religieux et existentiel’, in Les Grands Jours de Rabelais

en Poitou. [Actes du Colloque de Poitiers réunis par Marie-Luce

Demonet] (Geneva, 2006), p. 145-172. Jamet lived in Ferrara from

1535/6-1548, returning there once more in 1554 to assist Renée when she

was imprisoned (during an investigation of the Inquisition).

British Museum, Lansdowne Ms. 720. This Ms. has been ‘known’ always, but

only in the last part of the nineteenth century researchers began to pay

proper attention to it (Richter, Müntz, De Nolhac, Picot). Nicolas

Audebert travelled through Italy with recommendation letters from

influential friends and Latin poems from his father (Germain Audebert,

who had done a trip through Italy in 1539). Nicolas arrived in Turin on

22 October 1574 and left on 27 October. Adalberto Olivero, ‘Una

testimonianza trascurata sulla tomba di Clément Marot a Torino’, Studi Francesi 16 (1962), p. 263-265. A critical edition of Nicolas

Audebert, Voyage d'ltalie, appeared in two volumes, procured by

the same Adalberto Olivero (Rome, 1981), with extensive introduction,

bibliography and footnotes.

Olivero, ‘Una testimonianza trascurata…’, p. 264. In the critical

edition of Audebert, Voyage d'Italie, p. 141. Original: Ms.

Lansdowne 720, f. 37 r°/v°. We noticed some minor differences in

capitalisation and interpunction, and one corrected error (. Since

Olivero signaled that Jamet’s verse is written in a larger hand than the

rest of the text, we did the same in print. The text of the Epitaph

(except orthographical differences) is identical with the text of

Roville 1561 (Guiffrey/Douen); in the 1962 article. The transcription of

1981 differs in verse 5: “qui” instead of “que” (1962). Partial

translation: “…At the right-hand side of the church is a small door, in

front of which there is a pavement (or ‘landing’. French: ‘perron’) to

get into the church and beneath this pavement Clément Marot is

buried; his epitaph is nearby inside the Church, on a oblong

(rectangular) stone in the wall, which has only very recently been

chopped off and the Epitaph erased, on the explicit advice and request

of the Archbishop, and the masters of the Inquisition, with the approval

of his Highness, something which Milady the Duchess for a long time had

precluded, obstructing the plan when it was proposed…”

“qui

” (Bogarde 1546); “que” (Roville 1561).

“toute la” (Bogarde 1546); “toute” (Roville 1561).

Since 1560 the

Jesuit missionary

Antoine Possevino actively tried to re-catholicise the Waldensian

valleys. When the Duke restored the Turin University he recruted

professors of theology and metaphysics among the clergy and decreed that

members from the newly founded (1567) Jesuit college would teach the

humanities. (Paul F. Grendler, The universities of the Italian

Renaissance, p. 88-89). That the Duke organised the transfer of the

Holy Shroud from Chambéry to Turin in 1578, also speaks volumes, even

more because it apparently was staged to please the very pious bishop of

Milan, Carlo Borromeo.

Pour la petite princesse de Navarre, à Madame Marguerite, “Voyant

que la Royne ma Mere…” (Defaux I, p. 330). Jeanne d’Albret (ghost)writes

this letter to reassure her niece. The famous ‘Ma mignonne / Je vous

donne / Le bon jour…’ is meant to cheer up the same patient. For

Emanuele Filiberto, see P. Merlin, Emanuele Filiberto, un principe

tra il Piemonte e l’Europa (Turin, 1995) and for Marguerite de

France (or of Savoie), see R. Peyre, Une princesse de la Renaissance,

Marguerite de France, duchesse de Savoie, (Paris, 1902), awaiting a

new monography by Rosanna Gorris, Marguerite de France, princesse des

frontières. Poésie, éthique et politique à la cour de la duchesse de

Savoie (forthcoming).

Mayer, Clément Marot, p. 515. With this last phrase Mayer

probably refers to Lenglet’s initiative as does O. Douen in his book

about Marot and the Huguenot Psalter (vol. I, p. 443, footnote): “On a

vainement cherché son épitaphe dans l’église Saint-Jean, en 1731; il est

probable qu’elle avait disparu dès le

xvie siècle.” A

short summary of Olivero’s article, focusing only on the circumstances,

not mentioning the location, was published by H.P. Clive in his research

bibliography Clément Marot, an annotated bibliography (London,

1983), sub C 111.

We visited Turin on Monday 13 July 2009. The museum was closed (only

open on Friday-Saturday-Sunday) and we only had time to take a quick

look around and make some pictures.

The

Della Rovere family was “one of early modern Italy's most powerful and

influential historical families… a family of popes, cardinals, and

powerful dukes who financed some of the world's best known and greatest

artwork.” (back-cover of a collection of essays entitled: Patronage

and dynasty: the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy, ed.

Ian F. Verstegen (Truman State University, 2007). The most famous Della

Rovere pope is Julius II (Giuliano Della Rovere, pope from 1503-1513,

father of Felicia). Domenico became cardinal in succession of his older

brother Cristoforo, who in 1478 was made cardinal of Tarentaise by pope

Sixtus IV (Francesco Della Rovere, no direct family relation). Domenico

preferred the title of S. Clemente in 1479; he was transferred to Geneva

in 1482, but exchanged it for the see of Turin in the same year. In Rome

he acquired a chapel in the church of S. Maria del Popolo, which he had

Pintoricchio decorate. At his death in 1501 he was buried there, next to

his brother. Domenico’s remains were later transferred to Turin and

buried in the crypt of ‘his’ cathedral.

The bones of Anne de Crequi, (died 1541), the wife of

Sieur de Langey (Guillaume du Bellay, governor of Piedmont) were also

found and identified.

Next to the neatly labelled cases with the bones of Della Rovere and

other clerics in the crypt below the sacristy “[i] sotterranei del Duomo

custodivano altri tipi di sepolcri. Numerose lapidi, indicazioni sui

muri e incisioni attendono di essere studiate e messe a confronto della

storia. Oltre all’ossario degli ecclesiastici sono state rinvenute a

ridosso delle mura perimetrali lunghe sequenze di tombe a botola.”

Alberto Ricadonna, ‘Ecco l’ « altro » Duomo. Un magnifico complesso

liturgico e archeologico – La tombe di Della Rovere’ in La Voce del

Populo,

http://www.diocesi.torino.it/exdiario/altro_duomo.htm (last

modified, 10 September 2003; accessed 23 july 2009). This article was

published on the occasion of the completion of the restoration of the

crypt/ souterrain of the Cathedral. The supervising architect was

Maurizio Momo. It became clear that Cardinal Della Rovere had created

two churches, one upper and one lower church. A museum was instituted by

the diocese to give the people access to the souterrain of the Cathedral

and the discoveries made there. M. Momo wrote an official text to

introduce this museum: ‘Il Museo Diocesano. sede – restauri –

allestimento’.

http://www.diocesi.torino.it/museo/scheda.htm (last modified 13

January 2009; accessed 23 july 2009). The plans and photos are taken

from an article about the Museum by Don Natale Maffioli (in a brochure

in which Gianluca Popolla describes the way an ecclesiastical museum

should function), apparently meant to instruct the volunteers (‘corso

per volontari del museo diocesano di Torino’):

http://www.diocesi.torino.it/museo/volontari-museo-marzo09.pdf (last

modified 19 March 2009, accessed 23 July 2009).

Ceva is one of the many marquisats in Piedmont, itself divided in a

number of minor marquisats. It losts its independence (i.e. direct

feudal link with the Emperor) when Charles V granted it to the Duke of

Savoy in 1531. The text (entirely in majusculs): “hoc tvmvlo rari

splendoris dona ferv[n]tvr / hic e[st] christophorvs tvmvlatvs marchio

cevae / Cardineiqve nepos patris cognomine sancti / Cleme[n]tis sacri

templi reverendvs et hvivs / Canonicvs qvovis censendvs honore sacerdos

/ Moribvs: ingenio vita: probitate: decore. / Obiit xv maii m.d.xvi.”

The “a” from cevae is not placed correctely and twice a small majuscul

is needed to correct a mistake (“marchio” and “cardineique”). Standard

abbreviations are used. I was not able to identify a Cristoforo as

marquis of Ceva. For the history of Ceva, see Giovanni Olivero, Memorie storiche della città e marchesato di Ceva (Ceva, 1858). He

identifies this person as the son of Aria di Valarano della Rovere,

sister of the Domenico della Rovere, and Gio. Antonio Ceva d’Ormea. (o.c.,

p. 122. See also Ferdinando Rondolino, Il Duomo di Torino illustrato

(Turin, 1898), p. 171.

This epitaph is also carved entirely in majusculs. Abbreviations are

used, once with minor uppercase letters in superscript (SERMI]:

“Clavdivs gvichardus ara[n]dati dominus / ab intimis consilijs

svpplicibvsqve / libellis ser[enissi]mi, sabavdiæ dvcis hic / post

varios casvs ad / aeternam qvietem / qvuescit. / Soli fide deo vitae,

quod svfficit opta. / sit tibi cara salvs, caetera crede nihil. / vixit

annos li, dies xxix. / obiit die viii. maij: / m.d.c.vii”. Claude

Guichard (born around 1545), studied in Turin, was a close friend and

colleague of the (more famous) Antoine Favre. Guichard is mainly

remembered for his Funerailles et diverses Manieres d’ensevelir des

Rommains, Grecs et autres nations (Lyon, Jean de Tournes, 1581),

dedicated to the Duke of Savoy. He also translated Livius and published

Quatrains sur la vanité du monde, a poetic genre very popular at

that time in France. Intriguing is the adagium at the end of this

epitaph (“Soli fide Deo vitae quod sufficit opta / Sit tibi cara salus

caetera crede nihil.”: ‘Trust in God alone, desire from life what is

sufficient, Take good care of your salvation, for the rest fear

nothing’), not so much for the superficial resemblance to ‘sola fide’

but because it is quoted 50 years later by Guy Autret, Seigneur de

Missirien, in the dedication to the Bishop of Cornwall of his 1659

edition of Albert Le Grands Vie des Saints de la Bretagne. He

refers to this adagium as written by “un auteur pieux”, caracterising it

as one of the finest summaries of what faith is about ever written. (p.

xxii, edition Quimper, 1901). This suggests that it was published. We

wonder, did Guichard write it, publish it? or his friend Favre? or…?

The next epitaph (also on the left side of the door, but on the marble

pillar, just visible on fig. 1b) was carved out in an beautiful manner

as well including an ornamental layer. It is the epitaph of “Anto.

Adimarus” a famous Florentine (Antonio degli Adimari), who died 1528,

not only farther away from the door than the epitaph of Guichard, but

pre-dating Marot’s death as well.

|