|

Article published in

Renaissance

Studies, Volume 22 Issue 2, Pages 240 - 250.

[content the same, text slightly altered: minor corrections and some

expansions]

Did Clément Marot really

offer his Trente Pseaulmes to the

Emperor Charles V in January 1540 ?

ABSTRACT

In both popular and

scholarly literature, the offering of an early manuscript of the Trente

Pseaulmes by Clément Marot to the Emperor Charles V, passing through France

in the winter of 1539-1540, is presented as a matter of fact, often combined

with an identification of this manuscript with Ms. Cod. Vind. 2644 (Vienna,

Staatsbibliothek).[1]

The fact that this story is only known from one

source, the so called Villemadon Letter, dated 1559, is hardly

ever taken into account when referring to this event. This article raises

questions concerning the historical trustworthiness of the information contained

in this letter by sketching the historical background of it (the French Wars of

Religion), and the way the reference to the “Psalm offering” functions in the

propagandist discourse of the Letter. Finally the common identification of the

presentation copy with the Ms.Cod. Vind. 2644 is discussed.

KEYWORDS:

Clément Marot, metrical Psalms, French Court, Villemadon

Letter, Catherine de Medici, Huguenots

The story of Marot offering his Trente Pseaulmes

to the Emperor.

Although the verse translations of the

biblical Psalms by the French court poet Clément Marot are well known, not the

least because they form the nucleus of the later Genevan Psalter, much about the

genesis of Marot’s translation project remains unknown.[2]

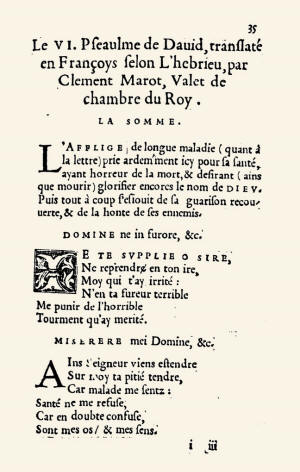

Material, mostly bibliographical, evidence indicates that probably around 1530

Marot translated the first penitential Psalm (Ps. 6) into French, which appeared

as a separate print and was added at the end of the second of the Augereau

editions of Le miroir de treschrestienne

Princesse Marguerite de France in 1533.[3]

This Psalm translation was also included in the sequel to

Marot’s collected works (La suite de l’Adolescence Clementine,

1534 onwards). Apart from this no official publication of any other Psalm

translation by Marot is known until the winter of 1541-1542, when Etienne Roffet

published Marot’s Trente Pseaulmes in Paris, accompanied by a dedicatory

Epistle to the French King.[4]

In the meantime though translations of Palms by Marot

circulated in, and even outside France. Manuscript copies, more or less hidden

references in his own poems, and unauthorised (partial) editions of the

Trente Pseaulmes (since 1539) strongly suggest an ongoing effort on Marot’s

part to add new Psalm translations to his first attempts.[5]

They also testify to an increasing popularity of Marot’s Psalm translations,

even though the atmosphere for translations of the Bible into the vernacular had

worsened considerably in the second half of the 1530s. In 1541 this unofficial

tradition culminated in a surreptitious edition of Marot’s 30 Psalms in a

collection of Psalmes de David in Antwerp in 1541.[6]

Noteworthy is that the text of Marot’s Psalm translations in all these editions

and related manuscripts differs considerably from the official edition by Roffet

(winter 1541-1542)..

Apart from this material evidence, hardly anything else is

known for certain about Marot’s translation activity. Nevertheless, almost all

scholars mention as a matter of fact that the Trente Pseaulmes were

presented to his King, Francis I, as early as 1539, and that the King was so

pleased with them that he subsequently suggested that Marot should present a

copy of the Trente Pseaulmes to the emperor, Charles V. The Emperor

visited Paris in January 1540 on his way to Flanders to suppress a revolt in

Ghent.[7]

It is also reported that Charles V received the Psalms gratefully, rewarded

Marot with 200 gold pieces, and encouraged him to continue the good work.

Consequently these verse translations became popular at court, with court

musicians composing music for them and courtiers trying to sing them to popular

or home-made tunes. As far as I can see, all authorities, historical, literary

and musical believe that this event did indeed take place. If a reference is

given, it is always to the so called Villemadon Letter and to this letter

alone.[8]

In this letter all the elements mentioned above are indeed present.

The Villemadon Letter [L. Cimber &

F. Danjou's reproduction (1843) I added as

PDF]

One would expect the historical reliability of this

apparently unique source to have long since been established beyond doubt, but

this is not the case. Nonetheless, V.L. Saulnier’s description of this letter

(dated 1559) as a fierce pamphlet against Cardinal Charles de Lorraine

comparable to Le Tigre of François Hotman, might have roused some

suspicions.[9]

Saulnier also wonders why its historicity is so uncritically

accepted: “Tout le peu de gens qui le citent délaisse, à ma connaissance, le

contexte, et a l’air de l’accepter comme d’office.”[10]

Though Saulnier questions the trustworthiness of many passages in this

letter, he accepts the reliability of the passage about the Psalms, because –

according to him – it belongs to a non-propagandist part of the letter and is

thus “gratuitous”. He recommends that its historicity be accepted until the

opposite is proven.[11]

I do not agree with Saulnier on this point and hope to make clear that the

opposite is indeed more probable; that is, the passage about the Psalms is not

gratuitous, but a substantial element of the propagandist discourse. An analysis

of the letter in its historical background seems the proper way to proceed in

order to be able to reassess the historical reliability of the narrative

elements concerning Marot’s Psalms.

Provenance of the Villemadon Letter.

The Villemadon Letter is dated 26 August 1559 and adressed

to Cathérine de Medici. The first known version was published in 1565 in an

anonymous Recueil des choses memorables...,[12]

a collection of pamphlets, manifestos and letters, which at the same time

document and serve the Huguenot war of the House of Condé against the House of

Guise (c. 1562-1568). The Letter might well have been such a pamphlet, and thus

it might antedate its first appearance by a few years. Unfortunately no one has

ever been able to confirm Ph.A. Becker’s promising remark, that he located an

original copy in Paris.[13]

The printer is identified as Eloï Gibier, and the place of print was

Orléans.[14]

The conception and publication of this letter is closely related to the first

War of Religion, which broke out around the death of Henry II (10 July 1559).

The introduction of the letter also explicitly links it to this period, not only

because of the date, but also in plain words. The writer himself characterises

the letter as a prophetic appeal to Catherine de Medici to break with the house

of Guise, since in his opinion they are responsible for the death of Henry II.

The memory of the past serves to reinforce this appeal. This does not

necessarily exclude historical reliability, but caution seems advisable.

The edition in the Recueil is signed “D.V.” The

identification of D.V. as a high court officer, named “Villemadon”, or “de

Villemadon” goes back to Louis Régnier de la Planche, who refers to the letter

in his Histoire de l’estat de France.[15]

This reference does not break the circle of Huguenot propaganda, since Régnier

de la Planche also an ardent Huguenot and prolific pamphleteer. Furthermore, the

identification itself is not much of a help, since according to Saulnier’s

research, no Villemadon or de Villemadon is known, either in the

entourage of Marguerite or in general. It is probably a pseudonym.[16]

Contents of the Villemadon Letter

[17]

The writer introduces himself as a former court official in

the household of Marguerite de Navarre. He often worked as an ambassador from

her court to the court of the King. He displays intimate knowledge of personal

and state affairs. He has long since

retired but, after the horrible

death of the king (Henry II died 10 July 1559), he

feels that it is his duty to warn Catherine,

for he has found out the “source et cause de l’infortune adveneu au feu Roy...

la vérité me l’a monstrée, comme je la vous feray toucher au

doigt et à l’oeil, discourant la tristesse de vos jeunes

ans, et le secours et faveur que Dieu vous donna...”[18]

The “tristesse” of Catherine to which he refers is the discovery that,

while her womb was barren (late 1530s), her husband Henry begot a bastard child,[19]

which inspired Diane de Poitiers (“la vieille meretrice”[20])

to organise a meeting of courtiers to persuade the king to repudiate Catherine.[21]

When Catherine found out, she could find comfort only in tears and piety.

She looked to God for help. The author addresses Catherine

directly: “en ce temps-là vous le recognoissiez, honorant sa saincte Bible, qui

estoit en vos coffres ou sur vostre table...”.[22]

Time went by. The King fell seriously ill and the enemies increased in power.[23]

It was then – still following the letter – that God decided to intervene and

save France by giving Catherine a child, the means to achieve

this, being the appreciation at court of the Trente Pseaulmes of Marot,

or as the author puts it:

[l’Eternel…] à l’instant va préparer et ouvrir le moyen par

lequel il vouloit que toute la bénédiction du Roy et de vous prinst naissance,

et sortist en perfection et évidence. Car ce père plein de miséricorde, meit au

coeur du feu Roy Françoys d’avoir fort aggréables les trente psalmes de

David, avec l’Oraison dominicale, la Salutation angélique et le Symbole des

Apostres,[24]

que feu Clément Marot avoit translatez et traduicts, et dediez à sa grandeur et

majesté;[25]

laquelle commanda audict Marot présenter le tout à l’empereur Charles-Quint, qui

receut bénignement ladicte translation, la prisa, et par parolles, et par

présent de deux cens doublons qu’il donna audict Marot, luy donnant aussi

courage d’achever de traduire le reste desdicts psalmes, et le priant de luy

envoyer le plus tost qu’il pourroit Confitemini Domino, quoniam bonus,

d’autant qu’il l’aimoit.[26]

Quoy voyans et entendans les musiciens de ces deux princes, voire tous ceux de

nostre France, meirent à qui mieux mieux les dictes psalmes en musique, et

chacun les chantoit.[27]

After Marot had offered his

Trente Pseaulmes to the Emperor Charles V on the explicit command of the

French King, his Psalm translations became an instant success at court,

everybody asking for a particular Psalm to call his/her own. Young Henry was

especially fond of Psalm 128, which blesses the man whose wife will bear him

lots of children (sic), and Catherine’s favorite was Psalm 142, a touching

complaint to the Eternal God.[28]

The author then relates that

he once paid a visit to the court and found Henry singing the Psalms with his

“chantres,” accompanied by all kinds of instruments.[29]

When he relates this idyllic scene to Marguerite, she not only praises the piety

and good faith of Henry and Catherine, but breaks out in

prophecy and predicts that for that reason God will turn their grief into joy:

“car,

puisqu’il a pleu à Dieu mettre ce don en leurs coeurs, voyci le temps, voyci les

jours sont prochains que les yeux du Roy seront contens, les désirs de Monsieur

le daulphin saoulez et rassasiez, les pensées des ennemis de Madame la daulphine

renversées; mon espérance aussi et la foy de mes prières prendront fin. Il ne

passera guères plus d’un an que la visitation miséricordieuse du Seigneur

n’apparoisse, et gageray qu’elle aura un fils pour plus grande joye et

satisfaction.”[30]

The author

concludes that Marguerite has been “une saincte sybile et véritable

vati[ci]natrice, d’autant que de treize à quatorze mois en là, vous enfantastes

nostre roy François, qui vit aujourd’huy.”[31]

Marguerite’s prophecy marks the transition to the last part of the letter

in which Charles de Lorraine is attacked vehemently.[32]

Influenced by him, the king abandoned the way of the righteous, the

Psalms lost their popularity, and therefore France has gone straight to its

ruin. That is why Henry had to end his days in agony.[33]

Thus the “source et cause de l’infortune adveneu au feu Roy”, mentioned in the

introduction to the letter, is unveiled. Once this mystery is revealed,

Catherine is urged to convert before it is too late, to do penance for her (and

her late husband’s) sins and begin again to serve God, as she did in her youth

by praying the Psalms of David, “reprenant en usage ces beaux psalmes

Davidiques, dont jadis vous réfrigeriez vostre esprit angoissé et pour lesquels

il vous béneict en génération.”[34]

She should chase away the treacherous clan of the Guises:

“Madame, voyez, allez; ne répugnez, ne permettez et souffrez que ce serpent,

diable rouge et ses adhérans, mettent la main au-devant [...]. Séparez et

esloignez de vous de tels monstres estranges.”[35]

In the end the author claims his words to be pure prophecy as well:

“Finablement, madame, pensez que mon dire c’est le dire du prophète; que si vous

ne le faites, vous verrez advenir en ce royaume tant de malheurs sur

malheurs...”.[36]

Summary and provisional

conclusion

According to the author of the

Villemadon Letter, Marot’s Psalms were God’s gift to save King Francis

and France. As long as they were cherished, France flourished. Precisely to

“prove” this, the introduction of the Psalms in France is surrounded with all

kinds of wondrous and wonderful stories, from a blessing of Marot’s Psalms by

the Emperor himself (including an exhortation to continue the job of translating

the Psalter[37])

to a prophecy of childbirth by Marguerite of Navarre. The fact that the turning

point in the history of France is symbolised once more by reference to the

Psalms is also telling. Did things change dramatically when Charles de Lorraine

got to grips with Henry II and replaced the godly Psalms of Marot with the

lascivous Horatian Odes? Well, they will change again if the use of the Psalms

is restored.[38]

This was a poignant discours in a period where Charles de Lorraine was very

powerful and the entire – by then Huguenot – Psalter had just been published.[39]

Based on this résumé, it seems

clear that the narrative about the Psalms cannot be considered as a gratuitous

detail in an otherwise highly tendentious letter, as Saulnier suggested. On the

contrary, it is a key element of the line of reasoning in the letter, and

therefore Saulnier’s advice to accept the narrative with a certain naïve faith

has become untenable.

The presentation of the Trente

Pseaulmes to the emperor is depicted as a public happening, immediately picked

up by the courtiers and court musicians. However, no reference to this event can

be found in contemporary sources, and this does not encourage us to credit this

narrative. Furthermore, the journey through France of the emperor and his army

(November 1539-January 1540) was one of the best covered events of the era, both

by participants and spectators.[40]

Finally, the fact that neither of the two Psalms cited in the Letter were

included in the Trente Pseaulmes does not add credibility to the

historical claim of the narrative. If not substantiated by external evidence, it

seems advisable not to accept the anecdotes about the Psalms in it as

established historical facts.

The manuscript of the

Trente Pseaulmes: Codex Vindobensis 2644.

If the manuscript offered by Marot to the emperor was

found, the story of D.V. would of course be confirmed. The only condition is

that a candidate must be linked, preferably

undeniably, to this event. At first sight, a manuscript of the Trente

Pseaulmes, now in the Vienna Staatsbibliothek, appears promising,

because it is not only richly ornamented (fitting for a gift to an emperor), but

also contains a full colour reproduction (I only could obtain a b/w copy) of the

coat of arms of the house of Habsburg.[41]

The first to link this manuscript to the story in the

Villemadon Letter

seems to have been Ph. A. Becker in 1921.[42]

This identification is, however, not unproblematic. Although the manuscript

indeed contains the coat of arms of the House of Habsburg, the catalogue of Otto

Pächt attributes it to Ferdinand I, Charles’ brother.[43]

Because of the presence of a one-headed eagle, the branch it represents is not

the branch of a Roman Emperor, but of a Roman King. Charles V never was a Roman

king. Ergo this manuscript was not dedicated to him, but probably to

Ferdinand I, who had been a Roman King since 1531. The main fields are those of

Hungary and Bohemia, but on the smaller inner shields (there are two!) things

get fuzzy.

[44]

But the reader may judge for him/herself since no exact

attribution has been made yet:

|

|

|

| Charles V |

Ms. 2644 |

Ferdinand I |

A second objection to this identification concerns the text

itself. The manuscript contains the Trente Pseaulmes of Clément Marot in

a version which is very close to the first official edition of Roffet (winter

1541-1542). This means that the natural temporal habitat of this manuscript is

somewhere in the vicinity of the Roffet edition, which is significantly later

than the events to which it is linked in the Villemadon Letter.[45]

We conclude that the mere existence of Ms. Cod. Vind. 2644 should not influence

the assessment of the historical reliability of the narrative present in the

Villemadon Letter.

Summary of questions

If the story of the presentation of the Trente Pseaulmes

to the Emperor in January 1540 were true, the next complex of questions would

remain without a satisfactory answer. Why do we find no contemporary reference

to the events as related by D.V.? Why did Marot keep the Trente Pseaulmes,

publicly blessed by King and Emperor, en portefeuille for two years? Why

did Roffet publish Marot’s welcome ode to the Emperor (“Cantique sur l’entrée de

l’Empereur à Paris”) in 1540, and not the Trente Pseaulmes at the same

time?[46]

The answer that publishing Psalm translations in the vernacular was a hazardous

project is always to the point in these dangerous years, with the exception of

this one moment in January 1540..., if the story of Villemadon were true.

Any objection from the Faculty of Theology would have been simply overruled by

the fiat of the King of France and the nihil obstat from the

“Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire”. It was a golden opportunity, a momentum...

if the story of the Villemadon were true.

Final conclusion

If one puts the events told by D.V. in parenthesis

(and all elements gathered here suggest that that might be a wise move),

everything seems to indicate that Marot never presented his Trente Pseaulmes

to the Emperor Charles V in January 1540. All the evidence, be it material,

textual or circumstantial, points to a different chronology, in which the date

of the first official publication (winter 1541-1542) is the anchor point.

In this chronology Marot dedicated the fruit of many years

of work, Trente Pseaulmes in French verse, to King Francis somewhere in

1541. He sent it to the king, accompanied by a dedicatory letter. Having

procured a Royal Privilege on 31 November 1541, Roffet published them and they

enjoyed a considerable success. The huge advantage of this simple chronology is

that no complicated theories have to be constructed to explain the fact that all

other Psalm editions and manuscripts known to us before this first official

edition, including the Antwerp Psalter of Des Gois, contain part of the

Trente Pseaulmes in quite a different version.[47]

This fact can be accounted for by simply stating that no other versions were in

existence at that time.

The Villemadon Letter should thus be regarded and

treated as what it is: a political pamphlet, which organises historical facts,

memories and legends, in a tendentious discourse, to create an effect on the

reader. This does not imply that there are no true historical reminiscences in

it that are corroborated by other sources (the initial popularity at court, the

professional musicians’ interest in it), but they all will appear to be more

naturally “at home” at a later date, that is after the first official

publication in the winter 1541-1542.[48]

Dick Wursten (Antwerp)

|